- Franz Waxman

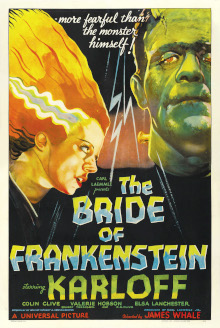

The Bride of Frankenstein: Danse Macabre (1935)

- NBC Universal (World)

orch. Clifford Vaughan

- 2[+pic].1[+ca].2[+bcl].1/2.2.0.0/2perc/org.hp/str

- 2 min 9 s

Programme Note

“It’s a perfect night for mystery and horrors. The air itself is filled with monsters.”

When Saturday afternoon audiences filed into their neighborhood theater to see Buster Crabbe in the latest chapter of the Universal serial, Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938), much of the background score might have seemed familiar to an astute moviegoer. It was Franz Waxman’s music, originally written for The Bride of Frankenstein (1935). Up until 1938, the American Federation of Musicians allowed the reuse of any music in the studio library for any studio film.

What made Waxman’s score so adaptable for re-working was the composer’s, extraordinary for its time, use of symphonic music for the horror genre, which translated easily to other Universal horror films and serials. The studios’ plunge into the horror cycle began in 1925, with the silent The Phantom of the Opera, and easily morphed into the sound era, with Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931). The latter two films made stars of Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff. Amidst all the subsequent horror excursions at Universal was the masterpiece, The Bride Of Frankenstein, with its angled sets and stark lighting. Karloff, climbing from the ashes of the burned-out windmill in Frankenstein, reprised his role as the monster (“I love dead – hate living!”), as did Colin Clive, as Doctor Frankenstein. The climatic sequence of the sequel is the birth of the ‘bride,’ accompanied by blinding electrical effects and the tolling of mock wedding bells, along with Waxman’s uses of a timpani to represent an obsessive heartbeat and ghostly string and wind tones.

Elsa Lanchester was memorable in her dual role of Mary Shelley and the ‘bride.’ Can you ever forget that marvelous zigzag lightning-streaked hair? Designed by director James Whale and actor Ernest Thesiger (Dr. Pretorious), Lanchester recalled:

“It was actually my own frizzy, untidy hair. They brushed it and combed it and made four little braids, and they put a sort of little house on top – a wire cage really – and anchored it with pins. Then they added two white hairpieces, one at my upper temple, another at my lower temple. It took two hours to draw in the little scars and go over them in red.”

Wisely, Whale was cognizant that this production was more ambitious in scope than the first Frankenstein, which he had directed, and cried out for an extended musical treatment, something more than the average ‘squeal and groan’ horror film scores. Having met composer Franz Waxman, at a stylish Hollywood party, and, being familiar with his music composed for the Fritz Lang-directed French film Lilliom (1933), Whale invited him to score the new visit to the monster and his friends. What Waxman created (the use of the word created seems to go with the theme of the movie), was a full-bodied, spine-tingling, hauntingly eerie, effective and groundbreaking approach. Composer Max Steiner had led the way into to this new world of dramatic underscoring of films with his music for King Kong (1933), and Waxman, in his defining addition to The Bride Of Frankenstein not only raised the bar but suggested limitless possibilities for the future.

The film premiered on May 9, 1935, at the Roxy Theater in New York, and is now widely considered to be the greatest gothic horror film of all time. When the last days in the life of director James Whale were turned into a film, Gods and Monsters (1988), it featured reconstructions of the filming of key scenes from The Bride Of Frankenstein. In fact, the title came from a line of Dr. Pretorious in the original, “To a new world of gods and monsters.”

— Jim Brown

Located in the UK

Located in the UK

Located in the USA

Located in the USA

Located in Europe

Located in Europe