- Franz Waxman

Ruth (1960)

(A Symphonic Suite in Three Parts)- Fidelio Music Publishing (World)

- 3(II,III:pic).3(III:ca).3(III:bcl).2+cbn/4.3(III:ram's horn[pictpt]).3.1/timp.4perc/hp[=2].pf(cel)/str

- 13 min 29 s

Programme Note

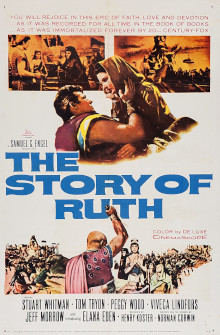

Samuel G. Engel’s production of The Story of Ruth, directed by Henry Koster, with a vibrant screenplay by Norman Corwin, is a recreation of the Biblical times. The cast includes Stewart Whitman, Tom Tyron, Peggy Wood, Viveca Lindfors, and Jeff Morrow, and introduces Elena Eden as Ruth. Waxman created one of his finest scores for this film and it became one of his favorite works.

The Old Testament’s brief account of Ruth is usually pointed to as a parable of tolerance and remembered with great affection. Her process of assimilation into the Jewish culture – complicated by suspicion of, and prejudice against, outsiders – arbitrates an even deeper lesson: it challenges the very notion of Jewish identity. Is the measure one of bloodline, or one of faith? In retrospect, this parable can be seen to have special meaning to the Jewish people of the mid-20th Century, when an enormous pogrom was sired from longstanding prejudice, and the subsequent effort to heal through the creation of a Jewish state in the traditional Holy Land met lasting resistance. That Ruth stands as a symbol of the will of Jewish culture to survive may explain why numerous projected feature films sought to tell her story; why one expensive production, The Story of Ruth, found its way to completion at 20th Century Fox in 1960; and why each of the principal figures in this production took such keen personal interest in crafting it artfully. It would not be unfair to suggest the most successful of these figures was composer Franz Waxman, for whom The Story of Ruth was a deeply personal experience.

The transformation of the Book of Ruth into The Story of Ruth was surprisingly convoluted, spanning nearly a decade and a half. The passage was instigated in 1946 by Herbert Kline. Kline began his film career as a documentarist and attracted considerable attention with Heart of Spain (1938, a look at the Spanish Civil War), Crisis (1939), and Lights Out in Europe (1940, chronicling the beginning of World War II in Germany). After the war, he traveled to Palestine to make My Father’s House, a fictional narrative that explored the birth of the Jewish State. His ambitions to make Hollywood films began to gain momentum at that time. On 11 August 1947, while in Hollywood to shop My Father’s House around to distributors, he announced his purchase of a screen adaption of Irving Fineman’s novel Ruth, hoping to produce it in the following year.

The enduring problems in adapting the Book of Ruth into a dramatic narrative are the brevity of the Old Testament’s tale – and the mandate to be scrupulously respectful of the tone and meaning of the sacred text. These concerns would haunt the efforts initiated by Kline through thirteen years of laborious writing aimed at carefully filling the many gaps in Ruth’s story.

In late 1951 Kline was still working on the idea, now under the title The Song of Ruth. A new screenplay was in development with writers Doris and Frank Hursley. Kline had just completed The Fighter, a boxing film starring Richard Conte, and made an enthusiastic pitch to Charles Feldman about the Ruth project. Associated with the successful Famous Artists Talent Agency, Feldman usually worked at packaging film projects which he then sold to others to produce than producing films himself. Films such as A Streetcar Named Desire, The Glass Menagerie, and Night and the City began as Feldman projects which were sold once he felt a viable script had been prepared. Feldman partnered with Kline on the Ruth project, but found it more than he’d bargained for.

The primary reason I made the deal with Kline was because Nick Conte told me Kline had a great picture in The Fighter. I thought I would gamble on it to the extent of $5,000. After seeing The Fighter, I came to the conclusion that [Kline] had no ability and the $5,000 had gone down the drain. I read the script and thought it needed a tremendous amount of work, which I have discussed and re-discussed with Kline….

Feldman engaged English writer and director Noel Langley to write a new screenplay. Kline went to London to supervise the work, completing a draft in November 1952. Though improved, Feldman was still unsatisfied and asked for revisions. Several other writers were hired to work on parts of it at the same time. Frustrated, Feldman wanted to get a renowned name involved in the effort. Just after New Year’s day, 1953, William Saroyan was approached with the idea, which elicited a brief response.

…if you can afford to pay what I think it’s worth -- $25,000 cash, plus a small percentage of world net – I will fix up Song of Ruth so that there will be a net – otherwise no use wasting valuable time.

That was the end of that. Maxwell Anderson proved to be more amenable and composed a screenplay by the summer. Still unsatisfied, Feldman brought more writers in through the next year to conflate the Langley and Anderson scripts into several new ones. Kline also took the initiative to work on the script again, still failing to satisfy Feldman.

By the winter of 1955, Feldman had an array of properties that had been worked over in script after script, and was looking to get out from under it all. Song of Ruth alone had cost over $78,000, with no immediate promise of a producible script. Having sold many properties to 20th Century-Fox, he turned to them with his catalogue. A complete buy-out of his operation took shape quickly, and Feldman proposed to buy Kline’s interest in the Ruth project in order to include it without difficulty in the sale to Fox. Kline relinquished his interest, retaining a provision that he would be paid $15,000 should the Ruth project go into production.

The sale of Feldman Group Productions was completed in September 1955, and the Ruth project went into limbo. Ruth tempted Producer Samuel G. Engel for some time before he succumbed.

It is a sweet, pastoral love story[.] It has an underlying theme of tolerance. It has the beauty of a lovely tone poem. But even if it was blown up, I couldn’t see it as a movie. [Then] I saw it as a movie with music[.] Boaz would be an older man, like Ezio Pinza in South Pacific, with music by Rodgers and Hammerstein. It could be beautiful, I thought. Boaz could sing something like “Some Enchanted Evening.” But then I figured it would be dull and I backed away from it.

Engel had been associated with 20th Century-Fox for a number of years as a writer and producer, and developed a solid reputation with My Darling Clementine, Sitting Pretty, Come to the Stable, Night and the City, A Man Called Peter, and Good Morning Miss Dove. By the mid-1950s he was in a position to form his own semi-independent production company in partnership with Fox. His interest in attempting an Old Testament subject was keen: he was eventually won over, and announced The Story of Ruth as the first project of Samuel Engel Productions on 17 September 1957. Ruth then endured another protracted round of writing. Shimon Wincelberg was immediately engaged to develop a new screenplay, which was completed by the end of November. Unsatisfied, Engel assigned the task to Michael and Fay Kanin on 28 January 1958. The Kanins worked on Ruth through the first half of the year, finishing on 28 June. Still unsatisfied, Engel then turned to Norman Corwin.

Corwin was a major liberal commenter on the American scene through the 1940s and 1950s, a reputation he forged as a pioneering radio dramatist long associated with CBS. After many ingenious dramas, CBS gave him a series, Columbia Presents Corwin, which featured many of the most famous actors of the day. He was a devoted Roosevelt democrat, and his commemoration of the end of the European war, On a Note of Triumph, commanded an audience of milestone proportions which necessitated a repeat performance a week later. His transition into screenwriting was not as productive, despite his gigantic success with Lust for Life, written for his long-standing CBS colleague John Houseman and director Vincent Minnelli at MGM in 1955. On 21 July 1958 Corwin started from scratch with a treatment titled The Loves of Ruth. Engel promptly announced this title as the intended one for his production. Corwin developed a screenplay from the treatment in the fall, finishing on 18 November. Rewriting consumed the following month, but by February he was starting over yet again. He finished another script titled The Story of Ruth on 23 April 1959, and this title was re-announced.

At last, there was a definite movement toward production when, on 1 July 1959, Henry Koster was assigned to direct a film of Corwin’s latest screenplay. Koster had directed The Robe in 1953, the religious spectacle that carried Cinemascope to the screen for the first time. Koster and Engel had worked together on several films; two of them – Come to the Stable and A Man Called Peter – were hailed as highly successful dramatic treatments of religious subject matter. Now they would jointly attempt a more ambitious project.

An elaborate search to cast the title character was already well underway. A press release for the production described the convoluted path to the chosen actress:

Between them, … Samuel Engel and … Henry Koster interviewed over 300 actresses for the part. They looked at film on as many more. They actually tested 29 actresses, 15 of whom were given black-and-white tests and 14 given full Cinemascope-color tests.

Then, discouraged, they suddenly decided to look at film on the chief contenders for the title role in George Stevens’ The Diary of Anne Frank. 20th Century-Fox casting director Owen McLean had spent 5 weeks in New York, 6 weeks in Europe, traveling through France, Holland, Germany, Austria, Italy and Israel in his hunt for “Anne Frank.”

In the film they looked at was 50 feet of black-and-white newsreel film and a two-minute separate dialogue recording of a beautiful, black-eyed, ebony-haired youngster from the Holy Land – Elana Lani Cooper, whom the studio renamed Elana Eden.

On that few seconds of newsreel film Elana so arrested the attention of Engel, Koster and script-writer Norman Corwin that they decided to test her for Ruth.

Elana, who had never been off the soil of Israel, flew to London, did the test, and it was so good that 20th Century-Fox Production Chief Buddy Adler signed her to a long-term contract whether or not she succeeded in winning the title role in The Story of Ruth.

Impressed also by the test, Engel and Koster asked her to come to Hollywood, where she arrived on 8 August 1959. She made two more tests while aware that other actresses were still being considered for the role….

Finally, on Rosh Hashonah (the Jewish New Year) Engel telephoned and greeted her with “Happy New Year, Ruth….”

Prominent among the other roles was Boaz. Stephen Boyd – made famous only months before for his role as Messala in Ben Hur – was to play the role, but was replaced by Stuart Whitman shortly before shooting started. The two maternal roles were well cast: Viveca Lindfors would play Eleilat, the Moab priestess who oversees Ruth’s training, while Peggy Wood would play the more substantial role of Naomi, Ruth’s mother-in-law.

Meanwhile, Corwin was engaged with stints of rewriting. On the same day Koster was assigned to the film, Corwin went back on the payroll. He completed a revised final script on 11 August 1959, and was brought back again on 2 November for three weeks, finishing just as production formally opened on 23 November.

Budgeted at $2,416,900 just after shooting started, the team resolved to hybridize their efforts at a Biblical melodrama. Advertising copy sought to promote the film along these lines:

…Most Biblical films are stupendous spectacles with gigantic battles, milk baths, and dancing girls. In contrast, The Story of Ruth is primarily a great love story and a great drama about tolerance.

Necessarily, since the period is spectacular to contemporary eyes, the costumes and settings seem so. And there are a few spectacle scenes – the Moab sacrificial ceremony and the quarry sequence.

But these are integral parts of the story, not forced in for the sake of spectacle. The emphasis is on realistic characterizations; warm, human relationships; and conflicts between people. The period may be Biblical, but what happens is applicable today.

Elaborate sets were designed by Franz Bachelin and Lyle R. Wheeler, and the film was shot for the most part on the Fox sound stages in a manner customary to Fox’s approach to spectacular filmmaking. Production continued until 12 February 1960, and the film was ready to be scored by the end of the month.

Franz Waxman was a friend and colleague to all three of the major figures in the production. Engel had produced Waxman’s first Fox assignment – Night and the City – in 1950; Koster directed My Cousin Rachel and The Virgin Queen, both scored by Waxman. Waxman’s friendship with Corwin was longstanding, as Corwin was part of a circle of close friends, including Bernard Herrmann and Victor Bay, who had socialized together regularly since the late 1940s. Corwin and Waxman worked on The Blue Veil for Jerry Wald’s production unit at RKO in 1951, and Corwin was the narrator in the world premiere of Waxman’s oratorio Joshua at the Temple Emanuel in Dallas on 23 May 1959.

With connections this profound it is hardly surprising Waxman was chosen for the film. Engel formally requested the Music Department engage him well before the cameras rolled. Waxman’s contract was written on 11 November 1959, the very day his contract for Beloved Infidel was closed. His fee was set at $17,500 for ten weeks’ work, with a tentative starting date of 1 February 1960. By 11 December it was clear a bigger window for the starting date was needed; Waxman was notified it would come between 25 January and 22 February. He did not actually start until 29 February.

Waxman worked steadily through the month of March and early April. His plan for the film involved an extraordinarily vivid instrumentation, including several rare instruments. Waxman fielded some of the difficult demands of his score on April 4th and 8th, when several players were called in for a rehearsal. These included bassoonist Don Christlieb, who owned an archaic brass instrument called the Serpent; and Milton Marcus, who owned a Taragato, a relative of the Eastern Oboe. Other novel choices included Bass and Contrabass Sarrusophones, which were a cross between the Saxophone and Bassoon developed in the mid-19th Century for use in marching bands. Each of these instruments has a nasal, penetrating tone that captures the archaic, middle-eastern tone appropriate to the drama. A large array of percussions were employed, and the halves of the film were juxtaposed in their sound worlds: Moab concentrated on winds, brass, and percussion, relying on short melodic motives and exotic, often dissonant, harmonies. Striking examples include “Chemosh,” opening with mysterious gongs which give way to equally mysterious arpeggiations for harps and celesta (0:28 to 1:16); the cue ends with devastatingly bizarre chords played by vibraphone, electric organ, and arpeggiated harps (at 2:39). Punishingly forceful expressions of Moab’s ruthless faith include “The Quarry” and the grotesque march in “Sacrifice.” Judea and the Jewish faith dwell in a more traditionally symphonic domain, frequently relying on sumptuous, divisi scorings for strings. One further novelty, employed briefly in connection with the character Mahlon (Tom Tryon), is the Viola d’amore, an 18th-century viola with seven strings supported by seven more thinner strings that enriched the tone of the instrument through sympathetic vibration. Though several violists in Hollywood owned violas d’amore, Waxman chose Virginia Majewski, who played passages such as the one found in “Second Meeting” (from 4:33 to 5:02) on her 1743 Klor, which she had previously played with extraordinarily beautiful results in Bernard Herrmann’s On Dangerous Ground in 1951.

Orchestrators Edward B. Powell and Leonid Raab began working the first week of April, and the first two recording sessions were scheduled for 21-22 April. These two sessions concentrated on the first half of the score. Sessions on 29 April 3 and 9 May filled in the rest of the score. A new version of the “Festival” music was recorded on the afternoon of 11 May, the last of the music to be recorded. Though generally delighted with the results, Waxman’s work was not free of controversy. For the pivotal scene of Ruth and Naomi’s flight from Moab back to Bethlehem, he chose to set Ruth’s famous proclamation for female voices (4:42 to 5:23) – rendered in contemporary language as “Where you go, I will go; your people will be my people, and your God, my God.” In late June of 1968, while delivering a eulogy at a concert memorializing Waxman’s untimely death the year before, Corwin circuitously described the disagreement.

In a spirit of public confession, I now bear witness to this. Once Franz was scoring a motion picture whose screenplay I had written. The score was beautiful – one of his best. But there was a particular scene for which Franz wrote choral music, and I objected to both the substance and form of the passage, as running against the grain, against the dramatic intention of the particular scene. It was a brash exercise of opinion on my part, since I was not the film’s producer or director, only its writer. Moreover, I stood almost alone – most others on the production liked the passage as written, some of them fervidly.

Franz was naturally hurt. Here I was, an old friend, making a good deal of static and crossing over into his province as he had never done into mine. We had an exchange of letters on it, diplomatic, polite, but mutually firm. Finally, a modification was made of that passage – a mild compromise over which neither Franz nor I felt entirely happy.

Now, in a case like that, the average composer might have resented my interference as arrogant. And maybe it was. An insecure composer would have felt challenged or injured or demeaned. It would automatically have ended a friendship. But not with Franz. We met at the preview, and he was warm and gracious. At that time I asked myself whether it was simply Franz’s innate dignity at the service of the occasion. But whatever doubts remained were dispelled when, [for a Los Angeles Festival concert in the summer of 1961], Franz invited me to narrate his oratorio Joshua…. I was honored by the invitation, but more than that, I was reassured forever that Franz harbored not the slightest trace of resentment.

The Story of Ruth was completed nearly $2,000,000 over budget, and released in June, 1960. Reviews tended to be modestly encouraging at best, and vicious at worst. Probably the most prominent review was that of Bosley Crowther, the film critic of the New York Times.

It should be apparent to anyone who has ever read the Biblical Book of Ruth that to get a screenplay from it a writer would have to do a lot of reading between the lines, then put his imagination to rather extensive use. As it stands, it is a curiously cryptic and temptingly stimulating book….

Where you would think a writer might have found for the background of Ruth something softly feminine and romantic, Mr. Corwin has made her out to be a somewhat metallic former high priestess of a pagan theology who backslides her own religion and is married to a Judean because of his more comforting [G]od. The two talk religion, not sweet nothings, when they get alone beneath the stars.

And you might think this same writer could have arranged for Ruth something sweet and perhaps a little racy with her late husband’s kinsman, Boaz, after she has been made a widow and fled to Bethlehem with her mother-in-law. But Mr. Corwin has mainly arranged for her to be charged with idolatry, a not very interesting defection. It is from this charge that she is freed by a virtuous Boaz.

All in all, Mr. Corwin has concocted a rather stiff and pompous dramatic account of how the great-grandmother of King David got over being a Moabite and got herself married to a Judean by lying beside him on the threshing floor. (Mr. Corwin has not even let her go to that modest extreme. He has kept the two at arm’s length, with only a tender look passing between.)

And Mr. Engel and Henry Koster, who directed, have followed a stiff and pompous line in putting a potentially romantic and poetic story on the screen. Their style, decorative and dramatic, is ornate, heavy and grim, pretentious of deep spiritual meaning but without convincing throb of flesh or soul.

It is hard to say whether Elana Eden, who plays Ruth, could successfully convey a considerable surge of emotion if she had a script and direction to spur her on. She is a pretty young lady, possessed of a very lovely and expressive pair of eyes. But without either a script or direction she is flat and mechanical, another automaton walking and talking through a Hollywood Biblical film.

The unfairness of blaming “the writer” for such comprehensive flaws – not to mention the sarcastically disrespectful tone – failed to escape unchallenged by Mr. Corwin. In a letter to the editor of the New York Times, published on 10 July 1960, Corwin retaliated against inaccuracies in Crowther’s review. He noted that the “not very interesting defection” of idolatry was “by far the most interesting defection in the entire history of ancient Israel. It consumed the passions, lives, and struggles of hundreds of thousands of people.” He also points out a significant gaff on Crowther’s part: “in the film, Ruth is not… ‘Freed from the charge of idolatry by a virtuous Boaz.’ ” On the contrary, Boaz very conspicuously fails to free her and a major story point is made out of this failure…. Furthermore, Boaz in the film is no “model of virtue”; he is introduced in the act of killing a suspect without the benefit of trial.” Despite Crowther’s inattentions to nuance, his complaints about the “stiffness” and pomposity of the film went unchallenged by Corwin. While these more esthetic claims might seem too subjective to debate, Corwin’s defense of the “factual” basis of his work reflects the deeper agenda of the film.

Ruth’s character is unique. Crowther implies that she dwells in the conventional role of the submissive woman. Actually, she is a person of pronounced political sensitivity and considerable courage. Trained as a priestess in Moab, she mastered the discipline of her culture. Her defection is partly emotional, a product of burgeoning maternal sensibility – but it is also philosophical, a product of her dialogues with Mahlon. She does not submit to defection out of desire; she judges it as her only ethical path. All manner of resistance fails to dissuade her from adopting a new culture – which she masters fully enough to defend herself shrewdly through cross-examination at a trial for idolatry. She has identified herself and selected the mate she desires, a worthy matriarch for a royal family. The longing for home and for a family was an acute part of the Jewish experience of the mid-20th Century, and obviously manifests itself here as a navigation of political and cultural anxieties that the film’s creators felt Ruth represented. Waxman may well have been in the most conspicuous position in this regard: the formation of his career occurred in Weimar Germany, and he personally experienced the violence of the approaching pogrom when he was attacked in the street by Nazi brownshirts shortly after Hitler’s ascent to the Chancellorship. He immediately went into exile, and founded his home and family in America with determination – and success.

Predictably, Ruth’s performance at the box office was ultimately very disappointing. Ben Hur, released the spring before production began on The Story of Ruth, stirred great hopes that Biblical films would do impressive business. By 1970 the film had earned $2,313,000 in domestic rentals and $1,892,000 in foreign rentals. Quickly retreating into film history, it is now remembered primarily for its rhapsodic score, and this was not slow to work in the composer’s favor. Shortly after the film was released, legendary cellist Gregor Piatagorsky saw it and was so struck by the many beautiful cello solos that he proposed to Waxman that a work for cello and orchestra be crafted from the film score. Sadly, this was never realized. Another admirer of Waxman’s achievement was Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who was soon swept into the calamity-plagued (and calamity-plaguing) production of Cleopatra. Waxman was sought for this film, and was keenly interested in it. But when its schedule extended again and again, Waxman eventually felt he simply couldn’t hold his schedule open long enough for the film to progress to the point of scoring. So Cleopatra became a conquest for Alex North, who won her with the feather he had earned from Spartacus. But, irrespective of the films themselves, Cleopatra and Ruth could hardly be more different. Waxman’s meditation on the latter was fortunate to find a faith burnished by maturity, and an artistry perfected by experience. Ruth’s companions are, instead, the Oratorio Joshua and the Cantata The Song of Terezin – all three of them key works of Waxman’s last decade, when he was at the height of his powers.

– Christopher Husted

Located in the UK

Located in the UK

Located in the USA

Located in the USA

Located in Europe

Located in Europe