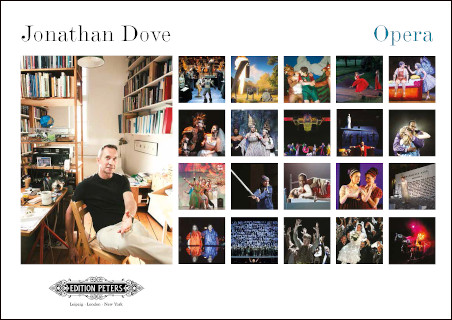

- Jonathan Dove

Mansfield Park (2011)

(Chamber Opera in 2 Acts)- Peters Edition Limited (World)

- Piano (4 hands)

- ColS,2S,C,2Mz,2T,2Bar

- 1 hr 45 min

- Alasdair Middleton and Jane Austen

- English

- 31st March 2026, State Botanical Garden of Georgia, Athens, GA, United States of America

- 1st April 2026, State Botanical Garden of Georgia, Athens, GA, United States of America

Programme Note

Synopsis

Mansfield Park is based on the 1814 novel by Jane Austen. The chapters and their titles are sung by the ensemble

Act 1

Chapter One: The Bertrams Observed. In which we meet the inhabitants of Mansfield Park.

Chapter Two: First Impressions. In which we discover that Miss Mary Crawford has twenty thousand pounds and that Mr Henry Crawford is not handsome.

Chapter Three: Sir Thomas Bertram's Farewell In which Sir Thomas Bertram leaves for Antigua.

Chapter Four: Landscape Gardening In which Mr Rushworth proposes a trip to Sotherton, his estate.

Chapter Five: In the Wilderness In which the estate is explored.

Chapter Six: Music and Astronomy In which songs are sung and stars observed.

Chapter Seven: Lovers' Vows In which Amateur Theatricals are undertaken.

Chapter Eight: Persuasion In which Edmund's resolution is tested.

Chapter Nine: The Rehearsal Interrupted In which Sir Thomas returns.

Chapter Ten: Independence and Splendour, Or Twelve Thousand a Year In which happiness is defined.

Chapter Eleven. A View of a Wedding, seen from the Shrubbery at Mansfield Park In which a wedding is celebrated, a honeymoon begun, a revelation made and plot hatched.

Act 2 Volume Two,

Chapter One: Preparations for a Ball In which Miss Fanny Price accepts a present from Miss Mary Crawford.

Chapter Two: A Ball In which partners are chosen.

Chapter Three: A Proposal In which the Bertram family are variously surprised, delighted, disappointed, confused and outraged.

Chapter Four: Some Correspondence In which much ink is spilt.

Chapter Five: Follies and Grottoes In which the Rushworths meet an old acquaintance.

Chapter Six: A Newspaper Paragraph In which occurs a matrimonial fracas.

Chapter The Last: In which Mr Edmund Bertram declares his feelings to his future bride.

Mansfield Park – the opera

When I first read Mansfield Park, over twenty years ago, I heard music. That doesn’t always happen when I read, and it certainly didn’t happen when I read other novels by Jane Austen. There was something about the storytelling in this particular book that created a space into which music naturally flowed. Perhaps it was because the quiet heroine, Fanny Price – so unlike the lively Emma Woodhouse, or the high-spirited Elizabeth Bennet – often appeared to suffer in silence. Her reticence invited the music; deep feelings, which she could not utter, were seeking expression.

Two scenes stood out for their eloquence, and although I can no longer remember the music I imagined for them all those years ago, I remember that they seemed especially poignant, and musical. In one, Fanny’s beloved Edmund has been distracted by the charms of Mary Crawford, but one evening joins Fanny in gazing out of the window at the stars. Fanny is overjoyed to be so reunited – but then Mary Crawford starts to sing, and Edmund is unconsciously drawn back into the room, away from the window where Fanny now stands alone, looking out at the stars. This follows the scene in which Fanny is left alone on a bench while Edmund goes off into the wilderness with Mary Crawford. Others follow suit and are compelled further into the wilderness, as if blown by immoral winds, while Fanny remains a still figure on her bench. Jane Austen’s understatement makes these scenes curiously vivid, and they have haunted me for years.

Around the time I first read the novel, some friends of mine were working for an opera company that performed in stately homes, using only a piano for accompaniment. Probably that is what suggested to me that this would be the perfect way of presenting Mansfield Park. Singing around the piano in a drawing-room is an entertainment which Jane Austen would immediately have recognized. Unlike the famous operas sometimes presented in stately homes, in Mansfield Park the piano would not be playing a reduction of something conceived for orchestra: the music would be imagined for a piano in the first place. I never thought of this as an opera for a conventional opera-house: I liked the idea that the stately home would itself be the set, and the action could happen all around the audience, and close to it. This would be a chamber-opera that really deserved the title: one that would actually fit into a chamber!

In this intimate setting there is no need to work the narrative up into something that more closely resembled grand opera; we could enjoy the subtleties of the novel and explore the drama that is already in the book. Alasdair Middleton made some radical decisions in writing the libretto: Tom would not appear, and there would be no scenes in Portsmouth. This made it possible to tell the Cinderella-like story in a single evening with a cast of ten. A surprising amount of what the characters sing is in Jane Austen’s own words. The music does not pretend to be exactly of the period, but I hope it suggests to twenty-first century ears something of the early nineteenth century, and the unique world of Jane Austen.

The opera was first performed in 2011, and has enjoyed productions practically every year since then (in 2019 there were five).

Jonathan Dove, 2024

Media

Scores

Features

- Operas in Concert: Classics of English Fiction

- Discover operatic works that shine in concert performance from Wise Music Classical.

Located in the UK

Located in the UK

Located in the USA

Located in the USA

Located in Europe

Located in Europe

Digital download

Digital download